Greater and Lesser Prairie Chicken

Kansas currently harbors two species of prairie grouse. The greater prairie chicken ( Tympanuchus cupido) is much more abundant than the lesser prairie chicken ( T. pallidicinctus). A third species of prairie grouse, the sharp-tailed grouse ( T. phasianellus) disappeared from it’s historic western Kansas range during the droughts of the 1930’s. Attempts to restore sharptails in the 1980’s and 1990’s, while initially promising, ultimately proved unsuccessful.

Prairie chickens may be best known for their unique spring breeding behavior. Early in spring, groups of males assemble on communal mating grounds known to biologists as leks. The low, booming sounds produced by greater prairie chicken cocks accounts for the common reference to their leks as "booming grounds." Similarly, the higher-pitched, bubbly sounds made by lesser prairie chicken cocks has conferred the term "gobbling grounds" to their leks. On a quiet spring morning, these sounds can carry as much as two miles across the open prairie, serving as an audible beacon to prairie chicken hens. Males of either species compete with each other through a series of spectacular displays, calls, and sparring for the coveted inner-most territories on the lek. The one or two males most successful in attaining and defending these small territories typically perform about 90% of the matings that occur on the lek. Unlike the polygamous ring-necked pheasant or the more monogamous bobwhite, prairie chickens do not form lasting behavioral bonds between cocks and hens.

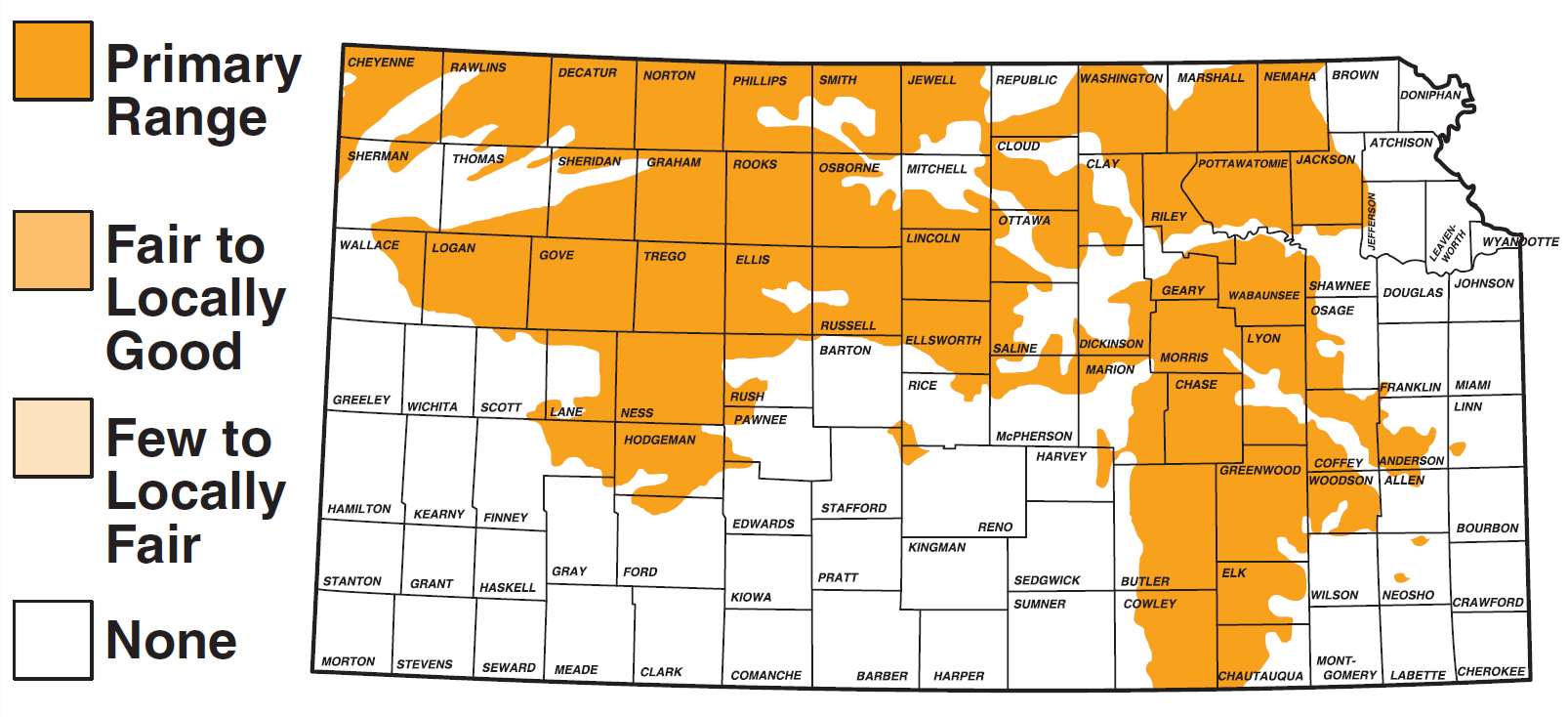

Greater prairie chickens currently occur in parts of 10 states, but by far the largest populations occur in Kansas and Nebraska. The traditional stronghold of greaters in Kansas is the Flint Hills, a roughly 50-mile-wide band of tallgrass prairie that extends from the Oklahoma border northward nearly to the Nebraska line in the eastern third of the state. The tallgrass prairie of the Flint Hills was saved from the conversion to cropland that consumed of most of North America’s original tallgrass prairie by its shallow soils and underlying limestone that resisted the plow. Strong greater prairie chicken populations also exist in the mixed prairies of the Smoky Hills in northcentral Kansas. Significant numbers of greaters can be found as well in the grassland breaks that parallel the streams of northwest and west-central Kansas. These western Kansas populations have increased and expanded over the last two decades, particularly with the addition of mixed grasslands seeded through the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

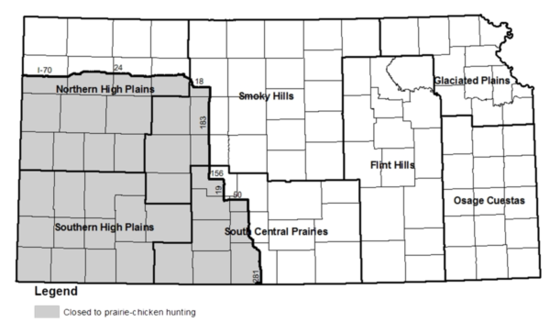

Lesser prairie-chickens are a bit smaller than their greater prairie-chicken counterparts. Prairie chicken hunting is not allowed in the Southwest Unit (see map) due to the lesser prairie-chicken being a species of conservation concern. Kansas currently provides habitat for the most extensive remaining range and largest population of the lesser prairie-chicken among the disjunct populations found in the five states where it occurs (Kansas, Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado). Lesser prairie-chickens still occur in Kansas' mixed grass and sand sagebrush prairies but their greatest densities can now be found north of the Arkansas River in a matrix of native rangeland and CRP grasslands. Lesser prairie-chickens were thought to have been extirpated from this portion of their historic range as recently as 25 years ago. However, the addition of CRP grasslands restored missing habitat components and populations of both lesser and greater prairie-chickens responded with range expansions and large increases in numbers. This expansion of lesser and greater prairie-chicken populations in west-central Kansas has brought these two historically overlapping species back together in a zone ranging from 20 to 40 miles in width. Some mixed leks with individuals of both species occur in this overlap zone.

Two distinct forms of prairie chicken hunting occur in Kansas. In the early portion of the season, hunters with dogs take advantage of the tendency for young prairie chickens to hold well at this time of year. Later in the fall and winter, prairie chickens gather into larger groups, often making it more difficult for hunters with dogs to get within gun range. During fall and winter, many prairie chickens feed in cut sorghum, corn, or soybean fields. Since these birds often fly directly to specific fields when they leave their grassland roosts in early morning, hunters can get pass shooting opportunities by positioning themselves at the margin of the field closest to the roosting area. This pass shooting method is the more common way of taking prairie chickens during the mid to latter portions of the season.

Prairie chicken adults are exceptionally hardy birds and are seldom significantly threatened by severe winter weather. Should deep snows occur, their ability to dive into the snow for roosting helps shield them from cold temperatures and wind chills above the snow surface. More significant weather threats to greater prairie chickens sometimes come in the form of excessive, drenching rains during nesting or when chicks are very small and most vulnerable to chilling. Drought is probably the greatest weather threat to lesser prairie chickens. Normal conditions in the range of the lesser prairie chicken varies from arid to semi-arid, so significant droughts can severely impact their habitat and production.

Historically, conversion of native prairies to cropland has accounted for the greatest loss of prairie chicken habitat in Kansas and elsewhere. More recently, other forms of human land use and development have posed additional threats. Particularly in the Flint Hills, the thorough annual burning of vast areas of tallgrass prairie associated with intensive, early cattle grazing in May, June, and July leaves few places for ground nesting birds like prairie chickens to successfully nest. Greater prairie chicken populations in the Flint Hills have declined significantly since this grazing system became widespread. However, less frequent burning, ideally once in 3 years or twice in 5 years, is critical to the health of the prairie and for prairie chickens. Possibly a more serious threat to greater prairie chickens and other grassland birds is the spread of invasive trees like eastern red cedar, Osage orange, and others into parts of our Kansas prairies ( read more: Tree Invasion). Ironically, this has resulted from too little application of controlled burning in some regions and from failure of land managers to quickly recognize and respond to the threat tree invasion poses to prairie, livestock production, and grassland wildlife.

Recent radio-telemetry studies conducted by Kansas State University researchers in southwest Kansas has highlighted yet another threat to prairie chickens. These workers documented a distinct avoidance of man-made structures by lesser prairie chickens. Generally, most prairie chicken hens avoided nesting or rearing their broods within a quarter-mile of power lines and within a third-mile of improved roads. Buildings, including a power plant and gas booster stations, were avoided from anywhere between two-thirds of a mile to one mile, depending on their size. This information, coupled with similar avoidance behavior noted in other species, suggests there is cause for concern over negative impacts on prairie chickens of other types of structures as well, including communications towers, wind farms, and suburban homes. Fragmentation of the open grassland horizons preferred by prairie chickens appears to represent yet another man-made threat to these species habitats.

Maintaining extensive tracts of open, well-managed prairie is critical to the conservation of prairie chickens. In Kansas, where 97% of the land is privately owned, ranchers are, unquestionably, the most important stewards of the prairies. Wildlife conservationists can best help conserve prairie chickens by forming alliances with ranchers to assist them in preventing tree invasion, to help them resist economic pressures to sell their lands, and to test new, economically-viable management systems that could prove more friendly to grassland wildlife. One such system with great promise is the "Patch Burning / Patch Grazing" system developed and tested by researchers at Oklahoma State University. Traditional grazing systems remain very viable for prairie health, provided they incorporate periodic fire ( not annual burning) and light to moderate stocking rates.

Greater and Lesser Prairie Chicken

Kansas currently harbors two species of prairie grouse. The greater prairie chicken ( Tympanuchus cupido) is much more abundant than the lesser prairie chicken ( T. pallidicinctus). A third species of prairie grouse, the sharp-tailed grouse ( T. phasianellus) disappeared from it’s historic western Kansas range during the droughts of the 1930’s. Attempts to restore sharptails in the 1980’s and 1990’s, while initially promising, ultimately proved unsuccessful.

Prairie chickens may be best known for their unique spring breeding behavior. Early in spring, groups of males assemble on communal mating grounds known to biologists as leks. The low, booming sounds produced by greater prairie chicken cocks accounts for the common reference to their leks as "booming grounds." Similarly, the higher-pitched, bubbly sounds made by lesser prairie chicken cocks has conferred the term "gobbling grounds" to their leks. On a quiet spring morning, these sounds can carry as much as two miles across the open prairie, serving as an audible beacon to prairie chicken hens. Males of either species compete with each other through a series of spectacular displays, calls, and sparring for the coveted inner-most territories on the lek. The one or two males most successful in attaining and defending these small territories typically perform about 90% of the matings that occur on the lek. Unlike the polygamous ring-necked pheasant or the more monogamous bobwhite, prairie chickens do not form lasting behavioral bonds between cocks and hens.

Greater prairie chickens currently occur in parts of 10 states, but by far the largest populations occur in Kansas and Nebraska. The traditional stronghold of greaters in Kansas is the Flint Hills, a roughly 50-mile-wide band of tallgrass prairie that extends from the Oklahoma border northward nearly to the Nebraska line in the eastern third of the state. The tallgrass prairie of the Flint Hills was saved from the conversion to cropland that consumed of most of North America’s original tallgrass prairie by its shallow soils and underlying limestone that resisted the plow. Strong greater prairie chicken populations also exist in the mixed prairies of the Smoky Hills in northcentral Kansas. Significant numbers of greaters can be found as well in the grassland breaks that parallel the streams of northwest and west-central Kansas. These western Kansas populations have increased and expanded over the last two decades, particularly with the addition of mixed grasslands seeded through the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

Lesser prairie chickens are indeed a bit smaller than their greater counterparts. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service added the lesser prairie chicken to the Threatened Species List in 2014, so prairie chicken hunting is not allowed in the Southwest Unit (see map). Kansas currently harbors the most extensive remaining range and largest population of the lesser prairie chicken among the disjunct populations found in the five states where it occurs (KS, TX, NM, OK, CO). Good numbers of lessers still occur in Kansas' mixed grass and sand sagebrush prairies but their greatest densities can now be found north of the Arkansas River in a matrix of native rangeland and CRP grasslands. Lessers were thought to have been extirpated from this portion of their historic range as recently as 15 years ago. However, the addition of CRP grasslands restored the missing habitat components and populations of both prairie chicken species responded with range expansions and large increases in numbers. This expansion of lesser and greater prairie chicken populations in west-central Kansas has brought these two historically overlapping species back together in a zone ranging from 20 to 40 miles in width. Some mixed leks with cocks of both species occur in this zone of overlap.

Two distinct forms of prairie chicken hunting occur in Kansas. In the eastern half of the state (east of U.S. Highway 281), an early season (Sept. 15 – Oct. 15) allows hunters with dogs to take advantage of the tendency for young greaters to hold well at this time of year. Later in the fall, chickens gather into larger groups, often making it more difficult for hunters with dogs to get within gun range. By fall, many prairie chickens will begin feeding in cut sorghum, corn, or soybean fields. Since these birds often fly directly to specific fields when they leave their roosts in early morning, hunters can get pass shooting opportunities by positioning themselves at the margin of the field closest to the roosting area. This pass shooting is the more common way of taking greater prairie chickens during Kansas’ regular season (3rd Saturday in Nov. to Jan. 31st, Daily Limit = 2). Since 1990, estimated greater prairie chicken harvests in Kansas have varied from a high of 59,000 in 1991 to a low of only 9,000 in 2002.

Prairie chicken adults are exceptionally hardy birds and are seldom significantly threatened by severe winter weather. Should deep snows occur, their ability to dive into the snow for roosting helps shield them from cold temperatures and wind chills above the snow surface. More significant weather threats to greater prairie chickens sometimes come in the form of excessive, drenching rains during nesting or when chicks are very small and most vulnerable to chilling. Drought is probably the greatest weather threat to lesser prairie chickens. Normal conditions in the range of the lesser prairie chicken varies from arid to semi-arid, so significant droughts can severely impact their habitat and production.

Historically, conversion of native prairies to cropland has accounted for the greatest loss of prairie chicken habitat in Kansas and elsewhere. More recently, other forms of human land use and development have posed additional threats. Particularly in the Flint Hills, the thorough annual burning of vast areas of tallgrass prairie associated with intensive, early cattle grazing in May, June, and July leaves few places for ground nesting birds like prairie chickens to successfully nest. Greater prairie chicken populations in the Flint Hills have declined significantly since this grazing system became widespread. However, less frequent burning, ideally once in 3 years or twice in 5 years, is critical to the health of the prairie and for prairie chickens. Possibly a more serious threat to greater prairie chickens and other grassland birds is the spread of invasive trees like eastern red cedar, Osage orange, and others into parts of our Kansas prairies ( read more: Tree Invasion). Ironically, this has resulted from too little application of controlled burning in some regions and from failure of land managers to quickly recognize and respond to the threat tree invasion poses to prairie, livestock production, and grassland wildlife.

Recent radio-telemetry studies conducted by Kansas State University researchers in southwest Kansas has highlighted yet another threat to prairie chickens. These workers documented a distinct avoidance of man-made structures by lesser prairie chickens. Generally, most prairie chicken hens avoided nesting or rearing their broods within a quarter-mile of power lines and within a third-mile of improved roads. Buildings, including a power plant and gas booster stations, were avoided from anywhere between two-thirds of a mile to one mile, depending on their size. This information, coupled with similar avoidance behavior noted in other species, suggests there is cause for concern over negative impacts on prairie chickens of other types of structures as well, including communications towers, wind farms, and suburban homes. Fragmentation of the open grassland horizons preferred by prairie chickens appears to represent yet another man-made threat to these species habitats.

Maintaining extensive tracts of open, well-managed prairie is critical to the conservation of prairie chickens. In Kansas, where 97% of the land is privately owned, ranchers are, unquestionably, the most important stewards of the prairies. Wildlife conservationists can best help conserve prairie chickens by forming alliances with ranchers to assist them in preventing tree invasion, to help them resist economic pressures to sell their lands, and to test new, economically-viable management systems that could prove more friendly to grassland wildlife. One such system with great promise is the "Patch Burning / Patch Grazing" system developed and tested by researchers at Oklahoma State University. Traditional grazing systems remain very viable for prairie health, provided they incorporate periodic fire ( not annual burning) and light to moderate stocking rates.

Forecast Factors

Two key factors impact the availability of upland game during the fall hunting season: the number of breeding adults in the spring and the reproductive success of that population. Reproductive success encompasses both the number of nests hatched and chick survival rates. For pheasant and quail, annual survival rates are relatively low; therefore, the fall population relies more heavily on summer reproduction than spring adults. While reproductive success remains the primary population regulator for prairie chickens, higher adult survival also helps sustain hunting opportunities during poor conditions This forecast will discuss the breeding populations and reproductive success of pheasants, quail, and prairie chickens. Breeding population data were gathered through spring calling surveys for all three species. Data on reproductive success were collected via late-summer roadside surveys for pheasants and quail, which quantify the number of adults and chicks observed. Assessing the reproductive success of prairie chickens is more challenging, as they do not typically associate with roads in the same way as pheasants and quail.

Kansas experiences a significant rainfall gradient, with average annual rainfall exceeding 50 inches in the far east and dropping below 16 inches in the far west. The amount and timing of rainfall are crucial for the reproduction of upland birds. In western Kansas, wet years generally improve available cover and increase insect availability for chicks. Conversely, in the east, dry years are often more favorable, as heavy rains during spring and summer can hinder the survival of nesting birds and young chicks. Above-average summer rainfall in 2023 across much of western Kansas greatly enhanced nesting cover heading into spring 2024. Continued adequate rainfall into mid-summer across the west provided good nesting and brooding conditions. As a result, production was significantly better than seen in recent years.

| Season | Open Dates | Daily Bag (Possession) | Open Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Pheasant | 2-3 Nov | 4 (8) | Statewide |

| Youth Quail | 2-3 Nov. | 8 (16) | Statewide |

| Pheasant | 9 Nov. – 31 Jan. | 4 (16) | Statewide |

| Quail | 9 Nov. – 31 Jan. | 8 (32) | Statewide |

| Prairie Chicken | 15 Sep. – 31 Jan | 2 (8) | Prairie Chicken Hunting Unit * see regulations for closed zone |

Pheasant – Pheasant populations have improved significantly across Kansas due to better nesting cover and favorable weather. Chick survival rates were high, thanks to an abundance of arthropods providing ample food, particularly grasshoppers. The high plains regions in the western third of the state saw the most notable increases, with some areas experiencing densities not seen in some time. The central prairie regions also saw improvements, though not to the extent of the high plains. While populations had been depressed by drought, the unexpected increases are promising. However, more time is needed for a full recovery. This year, acres enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) were again released for emergency cattle forage across most of the state. So far, CRP land hasn’t been as heavily used as in previous years, but it could still impact hunting success. Overall, pheasant hunting is expected to improve, and harvest numbers should rise. The best hunting opportunities will be in northwest and southwest Kansas.

Quail – Kansas continues to support above-average quail populations, with statewide spring densities remaining similar to last year. The summer brood survey showed significant increases in production. However, while quail numbers increased, the gains were not as large as those seen in pheasant populations. This is likely due to later peak nesting and less favorable weather later in the summer. Compared to previous years, the highest quail densities have shifted south. The Smoky Hills in north-central Kansas, which had the highest densities for several consecutive years, now has lower numbers than other major quail regions. The highest quail densities were observed in the Flint Hills and Southern High Plains, though good populations were reported across much of the southern half of the state. Kansas maintains one of the strongest quail populations in the country, and with abundant public access, the state is expected to have one of the highest quail harvests in the country. The best hunting opportunities will be in the southern half of the state, with quality spots scattered across other regions.

Prairie Chicken – Kansas is home to both greater and lesser prairie chickens, which require landscapes dominated by native grass with a few scattered grain fields. Greater prairie chickens are primarily found in the tallgrass and mixed-grass prairies of the eastern third and northern half of the state. Their numbers and range have recently expanded in the northwestern portion of Kansas, while declining in the eastern regions. Although prairie chickens are typically more stable than other upland bird species, prolonged drought conditions have reduced production, resulting in lower spring densities. Improved rainfall this year likely helped with production, but the areas with the highest remaining populations of prairie chickens did not recover as well as others. Despite this, hunting opportunities this fall will be best in the Smoky Hills region, where populations have remained most stable and public access to suitable habitat is more abundant.

The Southwest Prairie Chicken Unit, where lesser prairie chickens are found, remains closed to hunting. Greater prairie chickens may be harvested in the Greater Prairie Chicken Unit, with a daily bag limit of two birds. All prairie chicken hunters are required to obtain a Prairie Chicken Permit, allowing KDWP to better track hunter activity and harvest for management purposes.

Public Land: 12,849 acres

WIHA: 369,728 acres

Pheasants – This region saw significant improvements in roadside survey results this year. The High Plains has long been known for its pheasant populations but has experienced several consecutive years of below-average numbers. This year, dramatic population increases were observed across much of the region. Although many areas started from depressed populations, the increases were substantial enough to create good densities overall. Densities remained lower along the I-70 corridor, where the landscape is primarily cropland. Ample hunting opportunities exist as you move away from the interstate into mixed habitats, where higher densities were recorded. Since milo is less common in this region, hunters should target good cover such as waste grain or quality CRP adjacent to food sources.

Quail – Quail populations are limited and are typically harvested opportunistically by pheasant hunters. Weather patterns have facilitated population expansion in areas with suitable habitat, providing hunters with an additional opportunity in recent years. Summer roadside surveys indicated an increase in quail densities this year, particularly in the northeastern counties of the region, where hunting opportunities will be best.

Prairie Chickens – Prairie chicken populations recently expanded in both numbers and range within the region; however, drought conditions have significantly reduced spring densities. Only portions of this region are open to hunting (see map for unit boundaries). Production in the region was likely good this year based on upland bird production, which should enhance hunting opportunities compared to last year. Within the open areas, the best hunting should be found in counties along the Nebraska state line in native prairies and adjacent CRP grasslands.

Public Land: 106,720 acres

WIHA: 295,252 acres

Pheasants – This region showed slight improvement in the roadside survey but remains below the long-term average. Recovery from drought conditions has not been as rapid as in other parts of the state, limiting pheasant recovery, particularly in the north-central areas where densities have declined. Despite this, much of the region experienced similar increases to other areas of the state, leading to overall improvement. Quality hunting opportunities exist across much of the region, with the Smoky Hills likely to be a major contributor to this year’s overall harvest due to its size and accessibility. The southern and southwestern portions of the region will offer the best opportunities.

Quail – This region enjoyed several years of well above-average quail densities but has gradually declined since 2018, resulting in below-average fall densities this year. Spring densities were slightly reduced after poor production in 2023. While production improved this year and helped maintain populations, it was not enough to offset last year’s reductions. Although the region has lower fall densities than other major quail regions, it still offers a large area and hunting opportunities. Similar to pheasants, quail densities appear to be highest in the southern and southwestern portions of the region, where some improvements were noted.

Prairie Chickens – Prairie chicken hunting opportunities in the region are expected to remain fair. Production likely improved due to better precipitation, though conditions were not as favorable as in other regions. The area has maintained relatively stable densities and offers the greatest access in the state to suitable habitat. Greater prairie chickens are found throughout the Smoky Hills, where large areas of native rangeland are interspersed with cropland. The best hunting is expected in the central portion of the region, though several other areas support huntable densities of birds. The southwestern portion of the region falls within a closed zone (see map for unit boundaries).

Public Land: 51,469 acres

WIHA: 67,831 acres

Pheasants – Pheasant habitat in this region, including grass waterways and similar areas, has continued to decline. Pheasants were not recorded on any survey routes this year, and densities remain typically low, especially compared to other areas in central and western Kansas. Hunting opportunities will be poor, with pheasants found only in isolated pockets of habitat, primarily in the northwestern portion of the region or in areas specifically managed for upland birds.

Quail – Regional quail densities remain above average, although they have shifted within the region since last year. Previously, densities were more consistent throughout the area. This year, increases were observed in areas near large blocks of rangeland in the western portion, while the eastern part of the region, characterized by mixed cropland and woodland habitats, saw declines. With limited nesting and roosting cover throughout much of this region, targeting areas with or near native grass is essential for successful hunting.

Prairie Chickens – Very few prairie chickens are found in this region, and hunting opportunities are limited. The best chances for success are in the western edges of the region along the Flint Hills, where some large areas of native rangeland still exist.

Public Land: 109,883 acres

WIHA: 33,459 acres

Pheasants – This region is outside the primary pheasant range, resulting in very limited hunting opportunities. Pheasants are occasionally found in the northwestern portion of the region, but at very low densities.

Quail – Quality hunting opportunities should exist this year, particularly in the southwestern portion of the region. Roadside estimates indicated a slight increase this year; however, this was primarily due to improvements in the southern half of the region, which were offset by declines in the northern half. Some areas that previously experienced depressed populations remain low despite the overall improvement. Good densities of quail were observed in the southwest, especially adjacent to the Flint Hills. Hunting in this area is expected to be greatly improved, although much of the region will still have poor opportunities. Hunters should focus on grasslands that support quail or areas specifically managed for upland birds.

Prairie Chickens – Greater prairie chicken populations have consistently declined in this region over the long term. Fire suppression and the loss of native grassland have gradually reduced suitable habitat. While hunting opportunities are limited, prairie chickens can occasionally be found in large blocks of native rangeland, primarily along the edges of the Flint Hills.

Public Land: 196,901 acres

WIHA: 88,415 acres

Pheasants – This region is on the eastern edge of Kansas’ primary pheasant range and offers limited hunting opportunities. Pheasant densities have always been low in the Flint Hills, with the highest numbers found on the western edge of the region. Roadside counts decreased this year, with pheasants recorded on only one survey route. Given the limited densities and observed declines this year, hunting opportunities are expected to be limited. The best chances for success will be in the northwest portion of the region along the Smoky Hills.

Quail – The Flint Hills had the highest regional densities of Bobwhite from the summer brood survey. Reduced production last year resulted in slightly reduced, but still strong spring densities. After a dry year last year limiting habitat regrowth, burning was below average this year leaving more nesting cover this summer. Quail were able to take advantage of this cover and improved conditions to see considerable improvements across the southern Flint Hills, where the highest densities will be found. The northeastern portion of the region saw declines.

Prairie Chickens – The Flint Hills is home to the largest intact tallgrass prairie remaining in North America and has served as a core habitat for greater prairie chickens for many years. However, management practices involving too little or too much prescribed burning have gradually degraded habitat quality, leading to declining prairie chicken numbers. Burning was below average in 2024, which may have improved nesting cover. Production was likely better in the southern Flint Hills. Hunting opportunities throughout the region are expected to remain similar to last year.

Public Land: 41,125 acres

WIHA: 57,585 acres

Pheasants – Roadside survey estimates showed significant improvements across the region. While densities in the central part may have declined slightly, the majority of survey routes reported major improvements, with three routes observing pheasants that were absent last year. Although pheasant densities were low last year, these improvements are encouraging and will provide more consistent hunting opportunities throughout the region, though they did not lead to high densities overall. The largest pheasant populations will be found in the northwestern counties adjacent to the Smoky Hills.

Quail – Quail densities in this region experienced slight declines but remain relatively strong overall. Areas dominated by prairie saw improvements, while the central portion, which is more cropland-focused, experienced declines. The intermixing of quality cover types generally provides more consistent opportunities across the South-Central Prairies compared to other regions. The best hunting opportunities this year will be in the Red Hills, particularly along the Oklahoma border.

Prairie Chickens – The extensive rangeland areas in this region are largely closed to prairie chicken hunting (see map for unit boundaries). Prairie chickens are found in very limited areas elsewhere in the region at low densities. Encounters are unlikely but possible in the few remaining large tracts of rangeland in the northeastern portion of the region.

Public Land: 116,821 acres

WIHA: 143,071 acres

Pheasants – Similar to the Northern High Plains, this region experienced significant improvements this year. Last year, it was extremely depressed, recording the lowest regional densities among all major pheasant regions. Late summer rains in 2023 greatly enhanced nesting cover, and the ideal summer brooding conditions led to improved production, resulting in regional densities comparable to those observed in the Northern High Plains. CRP lands comprise a large percentage of the grassland in the region, and all counties were released for emergency CRP use again this year, which will likely impact the availability of huntable cover. Good hunting opportunities should exist across most of this region, particularly in areas with remaining high-quality CRP cover.

Quail – The quail population in this region is highly variable and dependent on weather conditions. Improved precipitation this year positively affected roadside estimates in the area. The highest quail densities are found along riparian corridors. Given this year’s roadside estimates, hunters should also have success targeting other woody structures or old homestead sites away from riparian areas. Scaled quail can also be found in the sand sage prairies within this region, but they make up a small proportion of the total quail population and have been depressed for the last couple of years.

Prairie Chickens – Prairie chicken hunting is closed in this area.

Conservation Reserve Program

Under the 2018 Farm Bill, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage cap has gradually increased each year. Currently, Kansas has approximately 1.96 million acres of CRP statewide. However, more than 486,000 acres of this total consist of grassland CRP, while traditional CRP acres continue to decline. This decline is largely attributed to lower rental rates combined with high commodity prices. Alongside the loss of acreage, the quality of habitat on the remaining acres is expected to be reduced. A total of 98 counties in Kansas have been released for emergency haying and grazing of CRP. A large portion of properties in Kansas' Walk-in Hunting Access (WIHA) and iWIHA programs include CRP land, and expirations/haying can reduce habitat quality or even exclude properties from the program. For 2024, Kansas' WIHA/iWIHA program has nearly 1.05 million acres enrolled. Atlases for these programs are available online at ksoutdoors.com/wiha and at locations where Kansas hunting and fishing licenses are sold.

Kansas has almost 1.7 million acres open to public hunting (Wildlife Areas and WIHA combined). There are more than 50 million acres of private land that also provide opportunity where permission can be obtained.